The Sad Saga of Schooner Bay, and How It Might End Well for the Bahamas

search the Original Green Blog

The foreign investor at Schooner Bay recently took the unthinkable measure of evicting the local organic farmer from Crown land that doesn’t even belong to Schooner Bay; who else do you know who is against healthy local food? But while the farm and the story surrounding it is highly regrettable, it’s not the biggest story here. Instead, the core issue is the question of how the Bahamas and also the entire Caribbean should be developing new places and healing old ones. But before that, here are some really important things to know about Schooner Bay:

Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, partners in business and in life, are the founding partners of DPZ and are widely regarded as the best planners alive on earth today. They are also co-founders of a worldwide movement known as the New Urbanism that seeks to build places that are compact, mixed-use, walkable, and sustainable, like our old towns and cities originally were. Andrés designed Schooner Bay with partner-in-charge Galina Tachieva and senior project manager Xavier Iglesias and an all-star supporting cast (plus me).

Many of you know me, but for Bahamians I may not have met yet, I’m the author of the book A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas], which was born out of my long love affair with Bahamian architecture; I’m now completing the second edition, which should be out by Easter. I have worked as a consultant with DPZ on countless projects over the past fifteen years, but of all those new towns and neighborhoods, I have long regarded three as the very most important: Southlands in Canada, Sky in the US, and Schooner Bay. The reasons for Schooner Bay’s inclusion in the top three are many, only a few of which I’ll mention here.

A Bahamian Town

Schooner Bay in happier days

When Canadian, US, or British developers or those further abroad think of developing in the Bahamas, their default model is the resort, but the Bahamas and the Caribbean are littered with the bones of dead resorts. Few resorts last even 50 years, and some fail much sooner, but Bahamian and Caribbean towns, on the other hand, usually last for centuries. DPZ designed Schooner Bay to be a Bahamian town where some of the houses are occupied by people on vacation, like Dunmore Town on Harbour Island, but where all of the businesses are run by Bahamians and many of the homes are occupied by Bahamians.

A Sustainable Town

Schooner Bay’s lush & carefully

planted dune, an important part of

resilience of the town in a storm.

Schooner Bay is designed to do so many things sustainably that this blog post couldn’t possibly describe them all, but it’s an important enough story that I’ve been blogging about it for years: The Schooner Bay Miracle tells why the place survived Hurricane Irene with hardly a scratch because of its hurricane-strong design. The Ecological Dividend lays out many benefits that accrue with time. Unfortunately, most developers do not practice patient place-making, and miss almost all of these benefits because almost everything in accepted development practice today stacks the deck against patience. All readers of this blog know that the first foundation of a sustainable place is that it must be a nourishable place, and Schooner Bay was designed to do ocean and farm to table as well as any place… at least until the foreign investor cut off the water to the farm last month. Today, there is a great rebuilding challenge in the southern Bahamas and all around the Caribbean, and the region sorely needs a great model, which is something Schooner Bay could have been and still can be.

A Diverse Town

Schooner Bay, a place designed for all Bahamians.

Most places built today have a very narrow range of home values, and are terribly boring as a result. Great New Urbanist places aspire to a range of values of at least 5:1 and sometimes as much as 15:1. Schooner Bay was designed to have an amazing value range of 40:1, which would make it much like Harbour Island, where Bahamians of all walks of life and foreign billionaires live just around the corner from each other. This makes a place not only far more interesting because of its diversity, but also far more resilient because neighbors can pull together after a storm much better if they have a great diversity of skills and resources. Harbour Island is a world-class model of how existing places can do this; Schooner Bay could be a world-class example of how new places could do this as well.

Bahamian Scale

This may sound superficial at first, but please hear me out: one of the great architecture mistakes foreign developers make in the Bahamas is building both homes and businesses to the scale of Dallas, Atlanta, or Orlando. In doing so, they make places that are totally out of scale with the Bahamas, and feel foreign and imported. People don’t come from Dallas to the Bahamas to experience a place that feels just like Dallas; they come for the Bahamas. A nation such as the Bahamas where tourism is the biggest industry should be very careful that both homes and businesses are built to Bahamian scale, like Schooner Bay was explicitly designed to be. Otherwise, visitors may decide to stay home next year.

A Town at the Crossroads

Four years ago, Schooner Bay's foreign investor David Huber terminated the role of Bahamian Town Founder Orjan Lindroth at Schooner Bay, as I later described in Schooner Bay at the Crossroads. I might have met Mr. Huber a time or two years ago although I don’t recall for sure, but certainly can’t say that I really know the man or his explicit motives. Some motives, however, are fairly apparent and all of them appear to go back to a fundamental misunderstanding of what Schooner Bay was meant to be. Mr. Huber, an American tech and communications entrepreneur with a checquered track record according to the Washington Post, clearly thinks Schooner Bay should be a resort, whereas it was designed to be a town instead. Every move Huber has made makes some sense for a resort, but are senseless for a town.

The good news is that very little damage has been done to the town plan in the past four years because only one building has been started in that time, and it wasn’t even completed when I was there mid-summer. All other changes are small and easily reversible. And for the good of everyone involved, it is time for that reversal to begin.

For Mr. Huber, I can’t imagine how much money he has lost with the place lying stagnant for four years, but that sum is likely dwarfed by his lost opportunity cost of time spent on a faraway real estate venture which is obviously not his passion, nor his expertise. I don’t see how Schooner Bay could be anything more than a distraction to him. I can’t imagine anyone on earth who would be more relieved for a transfer of ownership at Schooner Bay than Mr. Huber.

The homeowners and business owners at Schooner Bay would likely be almost as happy, as their investments that have lain dormant for these four years could spring back to life again as townbuilding begins anew. And there would be many benfits for neighbors around south Abaco as Schooner Bay grows into the town it was always meant to be, beginning with bringing the farm back to the Crown land, so south Abaco could benefit from having a local source of fresh food again.

The biggest beneficiary, however, would be the Bahamas as a nation. As Schooner Bay fully became what it was always meant to be, a shining village on the harbour serving as a world-class model of building sustainably in the tropics and sub-tropics, many would come from around the world to see the principles and practices of building sustainably laid out so clearly in one place. And the Bahamas could take on the mantle of underpinning and nurturing world-class models of sustainability at a time they are so sorely needed.

It is high time to get back to the tough but noble work of town-building at Schooner Bay. Everyone involved needs for this to happen. Soon.

~Steve Mouzon

PS: Here’s Andrés Duany’s poetic take on the earth, air, fire, and water of Schooner Bay.

You'll receive an email from me with the subject line "Mouzon Design: Please Confirm Subscription." Click Yes to confirm your subscription for A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] book updates.

Red Friday

search the Original Green Blog

photo by Charles Marohn, used with permission

Is this the beginning of the Fall of Sprawl? I was really struck by all the pictures on Twitter last night of half-empty shopping center parking lots yesterday, on Black Friday, which is the day American retailers finally get in the black (make a profit) for the first time of the year. But not yesterday. The final returns aren’t in yet, but when they are, there’s little doubt that most retailers will still be firmly in the red, many with little hope of turning a profit at all this year, making this the first Red Friday in America. The crash might come more quickly than anyone ever thought. Here are a few thoughts as to why:

Millennials Shopping

photo by Jon-Mark Patterson, used with permission

Millennials are notorious for not wanting to work in office parks. Many of them choose a cool city first, then a cool place in that city, then a job in that cool place. If they can't stand working in sprawl office buildings, then why would they want to shop in sprawl shopping centers? It's no secret that big retailers have been failing for several years, and what city isn’t littered with dead or dying malls? If yesterday really turns out to be the first Red Friday of our lifetimes, that could turn the stream of big retailer bankruptcies into a flood next year, because of the prospect of Red Fridays year after year.

Shopping & Sleeping

photo by Monte Anderson, used with permission

If you suddenly can’t shop in sprawl because there isn’t much left in a year or two, do you really want to sleep in that subdivision masquerading as a "bedroom community?” Remember the retail left in the inner cities in the 1970s once most shopping moved out to the sprawling new suburbs? It was mostly a collection of liquor stores, tattoo parlors, and cheap groceries with little more than unhealthy foods and cigarettes. It’s entirely possible that a similar thing could happen soon in much of sprawl if the shopping implodes. Who would want to live there then? Was today the beginning of the end of sprawl?

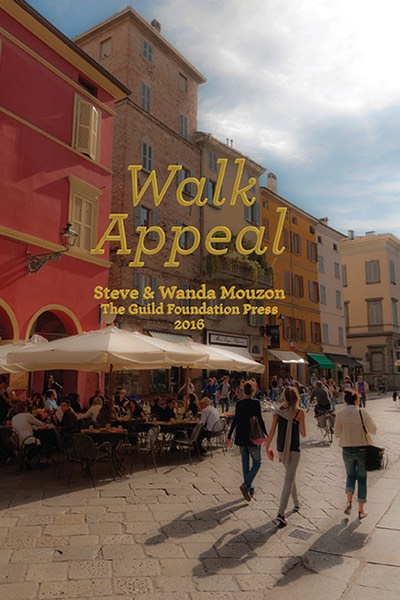

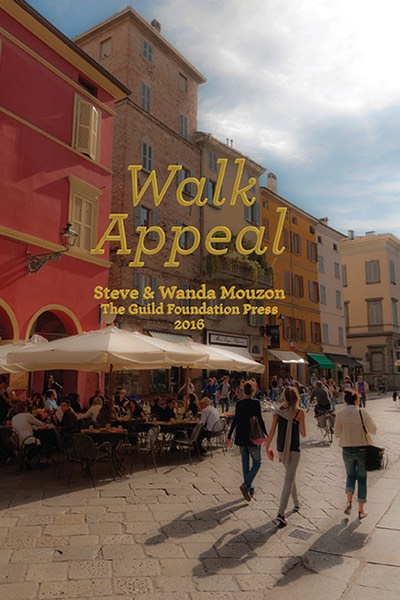

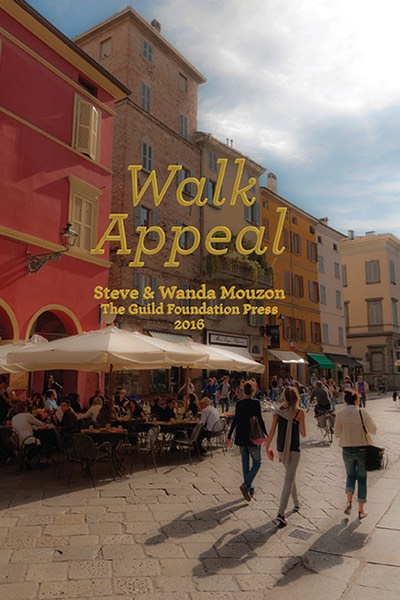

Traditional American Downtowns

On the bright side, retail in the USA has been an anomaly since World War II. European nations typically have 1 to 3 square feet of retail per person. It's now 41.6 square feet in the USA, although it was only a much smaller anomaly of 4 square feet per person here as late as 1960. And almost anyone who has ever been to Europe would agree that most of their urbanism is far more charming and vibrant than almost all of our sprawl. So getting rid of the seas of parking around the malls and replacing them with vibrant town centers that people might actually travel to for vacation (like they do to Europe) would be good, right? And to be clear, nobody in the history of the world ever decided to come to town on vacation because of the Walmart.

photo by Charles Marohn, used with permission

And lest this sound too Europe-centric, consider this: before sprawl began in earnest after World War II, no American town center contained more than about 17% retail, according to Kennedy Smith, who was the director of the National Main Street Center for years. The rest of it consisted of offices, workshops, restaurants, apartments, and other uses. So if sprawl and its retail collapses next year, it's really just taking us back to the classic American towns we loved so much. And the most of America which destroyed their most-loved places by trying to transform it into sprawl from 1945 through 1980 now cherishes their memories so much that the do the next-best thing by spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year to visit Main Street USA in Disney’s theme parks.

A Brighter Suburban Day

It’s entirely possible that many sprawling places will become ghost towns when they can no longer afford to keep up their infrastructure, as Charles Marohn and Joe Minicozzi have been saying for years. Fortunately, New Urbanists led by Galina Tachieva, Ellen Dunham-Jones, and June Williamson have responded to the alarm bells rung by Charles and Joe by crafting a suite of solutions now known as Sprawl Retrofit that can help transform forward-looking spawling suburbs with courage and political will into vibrant and sustainable places with high Walk Appeal and a diverse collection of local businesses to serve them. Because make no mistake: for at least two years, people have been turning to small local businesses instead of national chain stores. The Congress for the New Urbanism, which usually encourages its members to lead new initiatives, felt that this issue was so important that they took the unusual step of taking the Build a Better Burb initiative under their wing in recognition of the fact that retrofitting sprawl is now the biggest place-making challenge in American history. We simply cannot afford to fail.

~Steve Mouzon

Why Coastal Towns Must Thrive Now to Survive Later

search the Original Green Blog

The age of the sleepy little low-lying coastal town is ending. If a town with streets close to sea level hopes to survive into the distant future, it must plan to thrive in the near future. Anything less makes it a candidate for being a future ghost town. Here’s why:

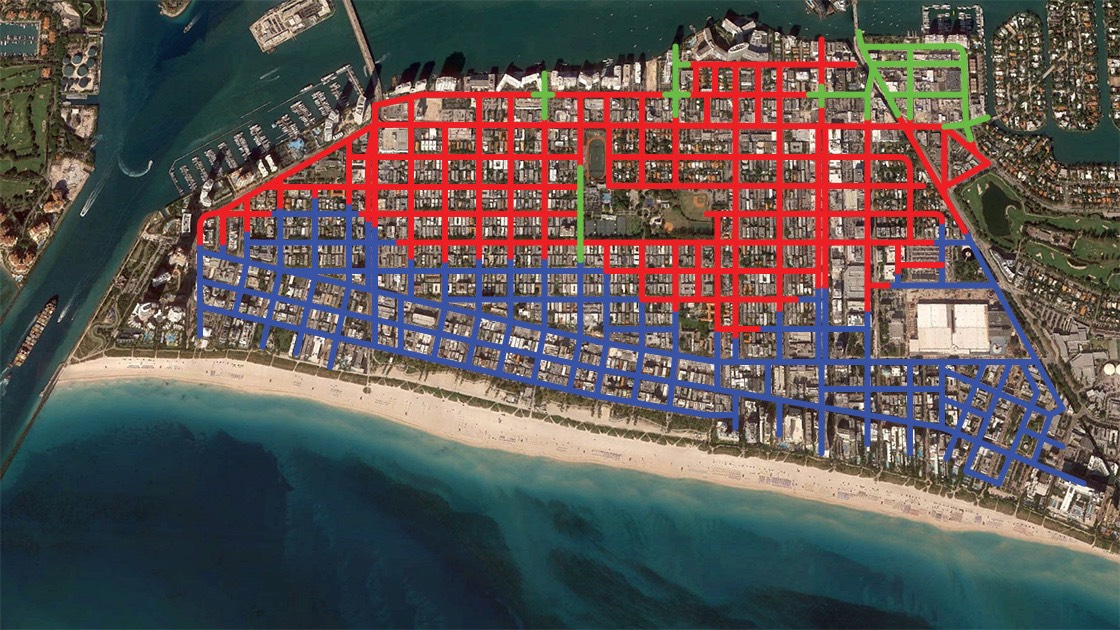

The image above is my adopted hometown of South Beach, which is only about a third of the City of Miami Beach. For the first few years after Wanda and I moved to Miami Beach fourteen years ago, “sunny-day flooding” was a term we never heard, nor did we ever see the phenomenon.

But beginning somewhere around 2009, we began to notice occasional puddles along streets on the lowest (Western) side of the island on days when there had been no rain. And by the time of the autumn King Tides of 2013, West Avenue was as deep as 18” in seawater. Google “octopus in parking garage” for an idea of what it was like. Here’s a video I shot on the worst night, when the waters of Biscayne Bay were literally higher than the streets.

Adapting to Sea Level Rise

11th Street being raised

Since that time, Miami Beach has begun a long-planned raising of the lowest streets, coupled with installing giant pumps and underground storage tanks. The blue streets above are 4.5 feet or more above a normal high tide, and should be dry for at least a century, depending on which scientists’ projections of sea level rise you use. The red streets above are less than 4.5 feet above a normal high tide, and need to be raised. The green streets have already been raised, although raising creates challenges as well.

Why have so few streets been raised? Because Miami Beach ran out of money to raise them. Obviously, many millions more need to be spent on raising streets, and that’s just South Beach. The rest of Miami Beach will roughly triple the expenditure. And we’re likely going to have to come up with most or all of it ourselves; we’re not counting on anyone to come in with a huge pot of money and save us.

Where will the money come from? Simply put, the city must thrive. We need to be doing everything we can now to transform sleepy neighborhood centers into vibrant places people want to come to, especially on the weekend, surrounded by interesting neighborhoods with neighbors who support the centers as well. Vibrant places generate far more tax revenue than sleepy places, and without that tax revenue, we simply won’t get all the streets raised in time. There are several ways of helping the city thrive. This post looks at characteristics of thriving town centers. Next, we’ll look at characteristics of neighborhoods surrounding those thriving town centers.

Thriving Town Centers

The most flourishing town centers on earth share a number of characteristics, and these should be patterns for coastal towns as their centers ramp up into economic engines that can help sustain them as sea levels rise.

Town Character

South Beach is “The 21 Most Exciting Blocks on Planet Earth.” New York City is “The City That Never Sleeps.” Seaside, Florida is “Capital of the Design Coast.” Unless your coastal town’s name is Palm Beach, you probably don’t have enough money in town to adapt to sea level rise without attracting visitors willing to come and spend money with you. If you want to live somewhere on the ocean and don’t want visitors, make sure it’s somewhere 25 or 30 feet above sea level so you don’t have to worry about adaptation anytime soon. Otherwise, figure out how to attract a lot of tourists willing to spend more than cruise ship passengers, who will not keep your town alive. To attract enough visitors who spend well, your town needs to be known for something. You won’t do well enough with visitors who just randomly happen upon your town along the highway; you should have a character of place that people want to experience.

Inexplicably, there’s a growing movement in South Beach to change the town character from The 21 Most Exciting Blocks on Planet Earth back into the sleepy little ethnic retirement community it was in the 1960s and 1970s. NIMBYs in nearly every neighborhood association are trying to get rid of the visitors, and cannot tolerate any noise at night. We will not survive very many decades into the era of sea level rise if these NIMBYs succeed. (NIMBY means Not In My Back Yard. The NIMBY’s big brother on steroids is the BANANA: Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything. Both are deadly to thriving towns.)

Arteries, Not Arterials

Vibrant Bay Streets, Main Streets, or High Streets are like arteries in a living creature, pumping the lifeblood of commerce and culture: people who are mostly on foot, enjoying all the things that line the street. But don’t confuse arteries with arterials. In the world of traffic engineers, arterials are the biggest and fastest automobile thoroughfares in town, and they are highly corrosive to all good things within a block or two in either direction. Instead of the sidewalk cafés and small-scale shops of Bay Street, arterials are usually lined with muffler shops, convenience stores, and drive-through fast food joints. Avoid these like the plague if you want a place that will thrive enough to pay the sea level adaptation bills.

people rarely walk between

fast-moving traffic & parking lots

Sadly, Miami Beach completely blew this on Alton Road, which could have been a great urban avenue lined with eating, drinking, and shopping establishments and thronged by people, like some of the other main streets of South Beach. And Alton is this way, for about a block south of Lincoln Road, but beyond that, it’s the same mind-numbing parking-lot-in-front-of-strip-center of suburban sprawl, with cars screaming by just beyond the sidewalk. The Flamingo Park Neighborhood Association staged an heroic battle with the Florida DOT for years to make sure their Alton Road rebuilding project increased Walk Appeal. And it looked like they had achieved a hard-won victory with the design until the DOT did a design switch at the last moment, inexplicably aided by City Hall. Until Alton is re-coded and rebuilt as a much slower avenue rather than the arterial automobile sewer it is now, Alton will contribute nothing to the vibrant character needed to help us pay for adaptation. Come and see it, then go home and do the opposite.

Building Character, Not FAR

Floor Area Ratio (FAR) is a planning standard commonly used by NIMBYs to oppose a project because they’ve forgotten what really matters. The most important thing is not FAR (usable interior square footage divided by site area), but the character of the buildings and how they support or corrode the streetscape. Every NIMBY wants to reduce FAR in order to build as little as possible on every site because the core assumption is that whatever the developer builds will be bad, so let’s at least limit it so we have less bad stuff.

The building in the photo above has an FAR of about 0.20, so the NIMBYs should love it. Never mind that it’s a completely banal and boring strip center… even though it was designed by the most celebrated Mid-Century Modern architect: Mies van der Rohe. This highlights the fact that the real problem arguably isn’t the developers so much as it is the architects. The refusal of my profession to design lovable buildings has spawned more NIMBYs than anything else in the past half-century. In this, the NIMBYs are not wrong.

Española Way in Miami Beach, on the other hand, has an FAR of just over 2.0 on several of its blocks. That’s ten times as much FAR as Mies’ strip center, and the architecture isn’t anything special. So using the NIMBY standard it must be ten times as bad, right? Have a look at these two images; which would you rather have as a neighbor?

FAR is an incredibly blunt instrument. Building character is what really matters. Some of the best urbanism in the world has an FAR of 3-5, as does some of the most hideous. The only definitive thing FAR tells us is whether a place has enough intensity to be a thriving neighborhood center or town center if the architectural character is good. Española Way’s FAR is enough for a neighborhood center frequented mainly by locals. For a great town center that will pull visitors in from elsewhere, you really need to get into the 3-5 range of great urbanism. Otherwise you simply don’t have enough stuff there to entice someone to travel to your center and spend money in your town.

Miami Beach is considering a measure in next week’s election to increase the FAR of an area Dover-Kohl has planned to become the town center of North Miami Beach. This should be a no-brainer for anyone interested in the long-term survival of Miami Beach. Unfortunately, the measure is receiving the normal complaints of “it will increase traffic,” but the complainers should look at South Beach. We have enough density here that over 40% of residents don’t even own a car because you need one so infrequently. Increase the density of the North Beach town center enough, and you’ll almost certainly see the same effect there. And it will help Miami Beach survive long into an uncertain future.

One more thing: these principles hold true in new places as well as old. With so many parts of the Caribbean Rim facing a huge rebuilding challenge after this year’s devastating hurricanes, these things should be considered there as well if the rebuilt places hope to survive long into that same uncertain future.

~Steve Mouzon

You'll receive an email from me with the subject line "Mouzon Design: Please Confirm Subscription." Click Yes to confirm your subscription for A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] book updates.

The Great Caribbean Rim Rebuilding Challenge

search the Original Green Blog

The Caribbean rim includes not only the northeastern and northwestern boundaries of the Caribbean, but also the “echo rim” of the Bahamas, the US Gulf Coast, and the Mexican Gulf Coast because all of these areas have heat, humidity, and hurricanes, and all have a heritage that is a gumbo of African, English, French, Native American, and Spanish cultures. The northern shore of South America is excluded because it is very rarely hit by hurricanes.

2017 approximate storm damage through early October shown as orange (serious) and red (severe).

As Caribbean Rim nations move from emergency relief to disaster recovery mode in the coming weeks and months, strong consideration should be given to the ways in which places should be rebuilt, both at the scale of towns and of buildings. This, the worst hurricane season in twelve years, has caused too much pain for too many people for everyone to go back to the ways things were before. The Caribbean Rim has had severe storms for all of recorded history, but many of the lessons our ancestors learned the hard way have been lost over the past century, as we moved from building in harmony with nature to trying to engineer our way out of severe weather problems.

Sustainable Towns

Sustainability begins at the scale of urbanism, because it makes no sense to talk about sustainable buildings until the place itself is sustainable. The lone surviving building in an uninhabited town isn’t a very good place to be.

Storm Surge

The first question to ask is “should we be building at all in this place?” This is especially difficult in a once-inhabited place that has been severely damaged, because it’s so hard to tell someone they can’t come home again. But the fact of the matter is that storm surge is one of the most destructive forces in nature, which building structures are almost powerless to resist. Strong storm surge almost always reduces buildings to piles of rubble, and usually kills more people than wind in a hurricane.

The good news is that storm surge risk is no longer a mystery, as we now have a good understanding of how the forces of nature and undersea topography affect the risk in any given place. Often, safer places are on higher ground within sight of surge-prone areas. Sometimes, it may be necessary to move a settlement a few miles away, but in no case should people return to places known to be at high surge risk.

Dunescape

A healthy dunescape is the first line of defense against a storm. Sadly, developers forgot that fact for decades and built right on the dunes in many places. When Hurricane Opal slammed the Florida Panhandle in 1995, many buildings in the vicinity Seaside, Florida were completely demolished, whereas Seaside was virtually untouched. Hurricane experts came to study what happened, and dubbed it the “Seaside Miracle.” The secret? Yes, the buildings at Seaside were built to stronger standards, but more than anything else, Seaside stepped back from and protected the dunes, unlike many of its neighbors. Hurricane Ivan hit further west in 2004, but still, buildings east of Seaside sitting on the dunes were destroyed while Seaside again experienced almost no damage.

Stepping back and not building on the dunes is only the first step, however. To sustain the dunes, it’s essential that they become diverse biomes instead of monocultures of single plants. Invasive species such as scaevola (sea lettuce) and casuarina (Australian she-pine) take over dunes and then destroy them. The best and most sustainable dunes have about twelve species of well-adapted plants, from grasses and ground cover to palm trees.

Agriculture

Until the mid-20th Century, most Caribbean Rim towns were fed from the fields and waters nearby. Now, most places on the Caribbean Rim and elsewhere are fed from thousands of miles away, and the shutdown of a single port facility such as the one in San Juan, Puerto Rico can result in food and other urgently-needed supplies not reaching those who need it most. Yes, a hurricane will damage the local crops, but if people have a choice between walking out into the fields and picking and eating what’s left of a crop today, or waiting for a ship to come in and get offloaded days (or longer) from now, which is more survivable?

Compact Towns

The benefits of compactness run far beyond the scope of this post, but some of the most obvious are as follows:

• Compact towns place buildings closer together, where each building helps shield its neighbor against hurricane winds.

• Buildings that are attached such as in downtown Nassau, Havana, and pretty much any Spanish colonial town are substantially stronger than buildings standing alone.

• Town centers with many attached buildings really should be built of masonry to resist fire spread, and masonry buildings are inherently stronger against the wind than framed buildings.

• Compact towns get electricity back quicker. We evacuated for Irma, and from the time we were allowed back onto Miami Beach until we got our power back was less than 24 hours. Last week, Wanda and I were in west central Florida near Apopka, and there were still many power lines down. This must ever be so, as utilities naturally try to get power back to the greatest number of customers as soon as possible, and that naturally happens where customers are closer together.

• Streets are walkable before they’re driveable. You can clamber over a downed tree on foot, but not in a car. If the town is compact enough, you can get to more necessary things sooner, by hours or more likely days.

• Fuel supplies in catestrophically-damaged places may be cut off for weeks, if not longer. Vehicles that survive the storm are of little use so long as they are out of gas. People in walkable places fare much better.

Small Local Businesses

Town economies built mostly on small local businesses tend to be more resilient than those filled with multinational chain operations for reasons we’ll explore in more detail in a later post, but some of the biggest reasons are:

• A local businessperson is far more motivated to get back in business because their livelihood depends on it, whereas to a multinational corporation, their location in town is just one of many around the globe.

• Decisions about whether and how to reopen a chain operation must be run up the chain of command to at least the regional level, which on the Caribbean Rim might be someone in another nation. Local businesses, on the other hand, need only find the basics like drinking water and fuel before they can start selling whatever is left of their stock of products.

• Chain stores tend to be larger, fueled by international business size standards and the myth that bigger is always better, whereas many local businesses on the Caribbean Rim are single-crew workplaces. Smaller operations have fewer employees (if any) and fewer moving parts necessary to get back in operation.

Local Leadership and Culture

This will be the topic of an entire upcoming post, but should be mentioned here as well. A town led by local leaders and guided by local culture is far more sustainable than a resort managed by an offshore corporation. The Caribbean Rim is littered with the bones of failed resorts, with hurricane damage being the most frequent cause of their demise. The outnumber Caribbean Rim ghost towns, even though people have been builiding towns for centuries longer than they have been building resorts.

Sustainable Buildings

Once a town is planned or replanned sustainably, it’s time to consider how to build or rebuild the buildings. A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] is a detailed pattern book showing how to build sustainably in the Bahamas, and most of the lessons from that book are useful around the Caribbean Rim.

Beloved Buildings

Almost everyone wants to put things back the way they were after a disaster. Their new home should look and feel like their old home. Unfortunately, many in my profession (architecture) want to remake the new world into something very different. This rarely succeeds, and even when it does due to a major source of outside funding (such as the Make It Right houses in New Orleans) it does not spread to surrounding neighborhoods simply because it doesn’t feel like home… it feels like something foreign. New buildings in Puerto Rico should not feel like they’re from Atlanta; they should feel Puerto Rican. New buildings in Barbuda (if the island is rebuilt) should not feel like they’re from Orlando; they should feel Barbudian. Not only do they help people recover emotionally from their losses, but they are more likely to be cared for and restored long into an uncertain future.

Buildings That Endure

Hurricane Design is a post that lays out several strategies for stacking the deck in your favor with building design. Here’s a quick summary of the top ten strategies:

• Build hip roofs on all but the smallest or strongest buildings to be wind-strong so each side supports its neighbors.

• Pitch wind-strong roofs 8/12 to 9/12 because this is steep enough to resist uplift but shallow enough to resist overturning.

• Overhang wind-strong eaves less than you would inland eaves so there’s less for hurricane winds to grab.

• When long eaves are necessary in the tropics, design them to blow off, leaving the main roof intact.

• Long eaves on wind-strong buildings can be supported by heavy brackets.

• Properly-attached metal roofing is the best material for a hurricane zone.

• Shutter windows in some way so that most if not all of the opening is protected with the shutters.

• Choose carefully between wood walls and masonry walls in a hurricane zone; each has its strengths.

• Build above the floods in a hurricane zone so the storm surge does little or no damage.

• If piers are masonry build them thick, or if wood, drive them deep so that they resist storm surges.

Kernel Cottages

Andrés Duany and I came up with the idea for the Katrina Cottages in 2005, on the Saturday after the hurricane. The original idea was to design “FEMA trailers with dignity,” but we quickly realized that with the money FEMA was spending to manufacture, install, commission, maintain, decommission, haul away, and dispose the FEMA trailers, we could design cottages worthy of being there for a hundred years, not just the FEMA-mandated 18 months. This would allow people to get a foothold back on their property, building on later to create a larger house.

Or at least that’s what we said. In reality, the cottages didn’t expand very well. Because the cottages were so small (several under 500 square feet) the exterior walls quickly got gobbled up with cabinets, closets, bathrooms, and the like so that it was difficult to find a place to add on. I designed the first Kernel Cottage the next summer; the very first design move was to put four “grow zones” in the plan, from which the cottage could expand. Disaster recovery housing that is mobile need not do this, but cottages meant to stay should definitely incorporate easy expansion.

Frugality

shelves built into a wall for storage - opening up

wall cavity also allows air circulation, reducing

mold & mildew

People recovering from a disaster are usually stretched to the limit (or beyond) financially. Why spend a lot of money conditioning a house if it can condition itself on all but the most extreme days of the year? An upcoming post will lay out several self-conditioning strategies. And self-cooling isn’t the only way to be frugal; you can be frugal with interior space as well, so that a cottage is smart enough that it lives bigger than its footprint. The New Urban Guild calls these SmartDwellings, and these are some strategies for implementing them. The image on that page shows an elaborate 1,200 square foot SmartDwelling, but the frugality techniques can just as easily be used on smaller Kernel Cottages as well. As a matter of fact, that’s where several of the techniques were first developed. We’ll dive into a number of frugality patterns in a later post.

Please Help!

This and the next several posts are things I’m writing for the second edition of A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas], which I hope and believe will be useful around the Caribbean Rim. The Original Green is a far better book because of many great comments I got from readers of this blog as I was writing it. Please help make this second edition a better book as well by posting your insights here… it could benefit so many people whose lives have been so disrupted! Thanks in advance!

~Steve Mouzon

PS: I made a mistake and lost all the original comments… here they are, copied in manually:

Orjan Lindroth · Nassau, New Providence

very much to the point an addresses issues we need to disucss, make aware and also practices we need to implement.

Steve Mouzon · Board Member at Sky Institute for the Future

Thanks, Orjan, and you're right, of course.

Oct 13, 2017 4:41pm

Steve, you might add the suggestion of a rainwater cistern to increase resiliency. It should be part of a circulating system, because still water goes skanky. The most beautiful version I've seen is in Bali, where there's an open concrete tank adjacent to the ( open air ) bathrooms, from which you ladle out water for your 'shower'. ( The design challenge is Westerners who mistake the cistern for a tub )

Steve Mouzon · Board Member at Sky Institute for the Future

Excellent on all counts, Bob... thanks! You describe it beautifully. I've never been to Bali (although Wanda has had it on our bucket list for years) so the best ones I've seen are in Bermuda, where the cisterns are a really expressive part of the architecture.

Oct 13, 2017 4:40pm

Kathy Gabriel · UWI St. Augustine

Implemntation of good ideas is always key ...

You'll receive an email from me with the subject line "Mouzon Design: Please Confirm Subscription." Click Yes to confirm your subscription for A Living Tradition [Architecture of the Bahamas] book updates.

The New Starting Point for Retail

search the Original Green Blog

Dinner Bell Barbecue on opening day

Burdening most new Main Streets with building the “climax condition” of 3-5 story buildings in the beginning is a poor choice in all but the most robust places, but going back to 1-story masonry buildings isn’t enough; the new starting point for retail should be the food cart. I recently returned from the NTBA Spring Roundtable, where there was great discussion on many things, including the future of retail. The single-crew workplace is the new high standard.

single-crew grocery in Beaufort, South Carolina

serves a neighborhood that would otherwise have

been a food desert

For a grocery, it’s one grocer in 500-800 square feet selling just the basic commodities like tomatoes, cabbage, spinach, one type of hot sauce, one brand of mustard, etc. For a restaurant, it’s one cook and one server. For the smallest possible B&B, it’s one person who’s clerk, cook, and housekeeper for four rooms. For the next size up, it’s one housekeeper for eight rooms and one clerk/cook. For a bar, it’s one bartender. For a coffee shop, it’s one barista. For a barber shop, it’s one barber.

Seaside’s iconic post office at the

heart of Central Square

We’ve seen great examples for years, like at Seaside, Florida, but keep getting charmed by the retail experts who base their projections on standard sprawl paradigms. Their arguments are compelling: “If you want to compete, these are things the market expects.” And they’re exactly right if you’re hoping to attract national retailers like Applebee's, Walmart, Bass Pro Shops, TGI Fridays, Walgreen, Best Buy, McDonald's, Publix, and the like. The problem is that if you want to compete in that arena, you’re committed to sinking millions into your infrastructure before seeing a dollar of return. Since 2008, that hasn’t been a very good approach for most of us. New retail centers would do well to compete in a very different arena.

Here’s another side of the problem with sprawl expectations: if you listen to the retail experts, you can’t even build a corner store until you have 600 rooftops. Seaside would never have achieved that because there will never be that many houses there, yet Seaside has become a thriving regional center. There are two secrets: Appeal to customers beyond your own rooftops, and start impossibly small with your shops, like Seaside did. A single-crew workplace makes many things possible today which are impossible until decades later using the retail experts’ standards.

Dinner Bell Barbecue the night before opening

for the first time

Our son Sam started Dinner Bell Barbecue recently in Portland, Oregon for amazingly less than you could ever start a bricks-and-mortar store. A conventional restaurant is at least an order of magnitude higher; usually much more. I’ve seen $100K vent hoods in my previous life as a small-town architect, so it’s really easy to spend a million dollars (in 1990s money) to start a restaurant.

In Sam's food cart pod, all of the food carts share a single toilet facility, and all utilities except electrical (which is overhead) gets piped around underneath the food carts. No, it’s not the most convenient, but yes, it’s highly frugal. This model is the future of inaugural retail in most places. If you’re going to CNU in Seattle, consider a side-trip to Portland to see this. It’s amazingly Lean. And food carts contribute substantially to Walk Appeal because your view changes every 10 feet or less, and often in very interesting and colorful ways.

Andrés Duany has been saying for several years that we need to scale back the inaugural condition of town centers, and Seaside’s Perspicasity and the Airstream shops courtesy of Daryl Davis have painted the picture of the future of retail for years. Why are we so slow to catch up?

~Steve Mouzon

How Fire Chiefs & Traffic Engineers Make Places Less Safe

search the Original Green Blog

All images in this post are from Celebration, Florida where scenes like this could soon look very different if the deputy fire chief and traffic engineer get their way.

Of all the urbanism specialists with tunnel vision, fire chiefs, fire marshals, and traffic engineers are probably the most dangerous. And by “dangerous,” I don’t just mean that they’re a threat to good urbanism; they also get people killed, which is exactly the opposite of what they are commissioned to do. A classic example of their silo thinking is playing out right now in Celebration, Florida, where the proposed measures of eliminating on-street parking spaces and eliminating street trees will almost certainly leave Celebration a less safe place than it is today.

Let’s look at things from both a common-sense perspective and a data-driven perspective. Getting rid of street trees does some really bad things for safety: First, it eliminates the first line of defense for those who are walking or biking on the sidewalk (when the streets are too dangerous for biking). A car crashing into a tree at 35 miles per hour will deploy the airbags, but the driver and passengers will likely walk away with little more than bruises. But a car traveling 35 miles per hour that crashes into someone who is biking or walking will likely kill them. Higher speed = more deaths and injuries.

Two groups injured and killed

most often are the young

(because they’re small) and the

elderly (because they’re fragile).

People adjust their driving according to the conditions around them. On a tree-lined street, people tend to drive slower because they don’t want to hit a tree if they lose control of their car and run off the road. Lower speed = fewer deaths and injuries.

There’s another problem with removing street trees: They make a huge difference between walking and driving in places that are hot in the summer (like Orlando). A canopy of street trees not only eliminates the strong radiant heat of the sun with its shade, but also cools you even further with the trees’ respiration, which has a similar effect to a cool mist. With a cooling canopy of street trees, most people walk well up into the 90s. With a hot sun beaming down, those same people rarely walk, even in the low 80s. But there’s another problem: humans get conditioned to everyday behavior, so when treeless streets condition them not to walk on moderately hot days, driving becomes their norm. And when you increase driving, you increase crashes and traffic deaths.

There are even more reasons not to eliminate street trees, but that’s another story for another day, because it doesn’t involve safety. On-street parking is equally essential to safety, and for even more reasons. As a matter of fact, on-street parking and street trees top the list of things cities should increase on streets if they’re interested in increasing the safety of their citizens. To be clear, the prime benefit of these two elements is getting people out of their cars because they prefer to walk to their daily needs. The two extremes are places where everyone drives (suburban sprawl) and places where everyone walks (European towns and villages). Where everyone drives, there are huge numbers of deaths per year because of crashes. In most places where everyone walks, nobody has ever died due to running into someone else.

Imagine this scene with all the trees cut down &

cars driving a lot faster.

Walking to daily needs is therefore the safe ideal; it’s stunning that the deputy fire chief and traffic engineer seeking to ruin Celebration don’t realize this. Here are the minutes of a recent meeting that illustrate their blindness to these facts. Note also how the officials talk out of both sides of their mouths. At one point, it sounds like they only want to remove one parking space closest to the end of each block, but when pushed, there are actually several entire streets where they want to remove all on-street parking.

This kind of double-speak is often found at the Department of Transportation. When the Flamingo Park Neighborhood Association was fighting the Florida DOT over the safety and character of Alton Road, the DOT finally agreed to put a landscaped median in the middle of Alton. But just before construction began, they released their final drawings showing that the “median” was actually two half-block-long turn lanes with one ridiculous palm tree in the middle of the block, where the turn lanes switched from one side to the other! In good DOT fashion, it was a classic case of “too soon to know” switching instantly to “too late to change.” I’m an optimist on most things, but I fear this tactic may be used to wreck Celebration.

shady Celebration sidewalk

On-street parking does several good things, and its alternative (on-site parking lots) does nothing good. Google “sea of parking.” Are any of the hits positive? Of course not; a sea of parking is dreadful on all counts. Beyond the obvious ugliness, they heat the microclimate by absorbing solar radiation and heating the air above them. Heating the microclimate makes walking uncomfortable and so people drive, even if the parking lot is out of sight. More driving = more crashes and more deaths and injuries.

“But what about on-street parking,” you might ask? “That’s paving, too.” Yes, it is, but it’s a lot less paving. Parking lots need travel lanes between the parking spaces. A 65’ wide perpendicular parking bay has two 18’ parking spaces and a 29’ travel lane. On-street parking needs no extra travel lane because the street itself is the travel lane. So off-street parking requires almost twice as much asphalt and destroys almost twice as much green space as on-street parking, heating the microclimate almost twice as much, discouraging walking and encouraging driving. More driving = more crashes and more deaths and injuries.

If parking lots were all put in the middle of the block, it would do less damage to the urbanism because it wouldn’t be visible from the street. Unfortunately, parking is far too often put in front of the building, just behind the sidewalk. If the street is heavily traveled, this creates the dreadful W0 Walk Appeal condition where people simply do not walk unless their car breaks down. Parking lots in front kill walking and increase driving. More driving = more crashes and more deaths and injuries.

Celebration sidewalk cafe protected by street trees

On-street parking makes sidewalk cafes possible. It would be insane to have lunch sitting at a table where cars were zipping by at an almost-certain-death 35 miles per hour just a foot from your elbow. But with cars parked alongside the street, moving traffic is much less of a threat. Sidewalk cafes are both the highest indicator and the highest single stimulus of Walk Appeal, which is the best indicator of places where people walk more and drive less. To make a place safe, we need more of them. I haven’t done the research yet (that’s for a later post), but there’s a strong likelihood that places with many sidewalk cafes have fewer deaths by automobile per capita than those with none. Less driving = fewer deaths by automobile.

Walk Appeal is the strongest indicator of the likelihood of success of neighborhood businesses in walkable places. When businesses succeed in walkable places, more neighbors patronize them on foot and people drive less. Less driving = fewer deaths by automobile.

Without street trees, asphalt on the

street on the left would be soaking

up heat all day long, and therefore

heating up everything around it.

Similar to street trees but even more powerful, on-street parking (especially diagonal parking) reduces driving speed. The possibility of a parallel-parked car opening a door in front of you subconsciously slows you down; the possibility of a diagonally-parked car backing out in front of you does so even more effectively because that would be a worse crash than just knocking someone’s doors off. If a car strikes you traveling 20 miles per hour, you’ll likely suffer some bumps and bruises and maybe a broken bone or two; if a car strikes you traveling 40 miles per hour, I hope you have your things in order, because your family and friends will be burying or cremating you in a few days. The US DOT is the source of this information (scroll down to the Vehicle Impact Speed vs. Pedestrian Injury chart). Lower speed = fewer deaths and injuries.

It is insane that most traffic engineers don’t understand this! And their prejudice against safer design is cooked right into their standards: the AASHTO Geometric Design of Highways and Streets (the "Green Book,” which is the bible of traffic engineering), uses the Level of Service (LOS) system where streets are rated from A to F with A being best and F being worst, like grades in school. Here’s the problem: LOS A is the free flow of traffic at the highest speeds (most deadly), while LOS F is a slow-moving traffic jam (safest). Speed kills… especially if you’re walking or biking. Higher speed is OK if you’re driving on an expressway through the countryside, but it’s decidedly not OK if you’re driving in a city or town. To be blunt, the Green Book standards have probably killed hundreds of thousands of people in towns and cities. It’s deadly. Put a less dramatic way, the Green Book is great for highways in the country, but not for in-town streets. For that, you need Designing Walkable Urban Thoroughfares, a design manual jointly created by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE) and the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU). Sadly, many traffic engineers have apparently never heard of it, even though it reduces deaths and injuries in town, while the Green Book increases deaths and injuries in town by speeding up traffic. Higher speed = more deaths and injuries.

The deputy fire chief never actually said “cut the trees

down.” He just said to remove them. But there’s

no way you could move trees like these with

any chance of them surviving.

This brings up another problem: eliminating on-street parking makes wider travel lanes. Of all the factors affecting travel speed, there is none more reliably calibrated than lane width. People behave differently in different settings. 9-foot travel lanes induce all but the idiots to drive no more than about 20 miles per hour. It’s important to note that you can never design for the idiots, because there’s no way to predict what someone will do when they’re in an irrational state of mind. On 10-foot travel lanes, people tend to drive 20-30 miles per hour. 11-foot travel lanes should only be used on the highest-speed thoroughfares in town, where there is good protection (like high levels of on-street parking) for people walking. 12-foot travel lanes are Interstate lanes, and we all know how fast people drive on the Interstate. In town, 12-foot travel lanes should be called “death lanes.” Higher speed = more deaths and injuries.

Now, let’s look at some numbers. And this is just the first in a data-driven series of posts. It looks broadly at nationwide numbers for general trends. Later, we’ll compare urban form: cities with tight-knit traditional urbanism versus cities built mostly of sprawl. From a fire perspective, one would think that the USA, built mostly of modern buildings on broad streets where large fire trucks can turn easily and where most buildings are built to modern fire codes, would perform far better than European countries, which are burdened with medieval urbanism, with narrow, cranky streets and small-pipe water. Here are the recent facts, all from 2007 (the last year for which I was able to get data for all these nations):

Celebration's post office is one of

many walkable destinations. If

walkability is damaged and more

people drive, there’s probably not

enough parking for them all.

Fire deaths per million citizens:

USA: 12.4

France: 9.8

UK: 7.6

Spain: 5.2

Italy: 4.2

So US fire deaths are over 20% higher than the highest of the Western European countries selected and almost triple the deaths in Italy. I wasn’t cherry-picking; I chose the most populous countries in Europe nearest the US. Germany, for example, is substantially lower than Italy.

So the wealthiest country in the sample with the most modern buildings performed worst on fire deaths? Meanwhile, the other countries have buildings hundreds of years older, serviced by cobbled-together electricity and built on streets so narrow that many of them would be considered alleys in the US performed substantially better? How can this be? I’ll post later on the details of fire risk and urban form, but unless the Europeans are fantastically smarter than Americans and have much better reaction time, how else do you explain this huge discrepancy other than as a product of urban form? I suspect the primary cause of this difference that is costing over a thousand American lives per year is the difference in urban form.

It only makes sense that places requiring four times as many miles of streets per person (or more) would be harder to protect, even if the streets are wider and allow faster fire truck travel. If that’s the case, fire departments should be celebrating places with traditional urbanism like Celebration, and bending over backwards to support that urban form (including buying smaller fire trucks) because it makes them look better by being substantially safer. Instead, they’re punishing traditional urbanism and trying to damage it enough to bring it back to the unsafe standards of American sprawl.

It gets worse. Let’s look at those same five nations through the lens of death by automobile. If traffic engineers touting Level of Service standards were to be believed, the US should be the safest nation because more of our thoroughfares have been built to these modern standards. Meanwhile, Europe with its narrow, cranky streets should be really unsafe. Here are the facts, all from 2014 or 2015:

Every comfortable destination that becomes

uncomfortable by cutting the trees down becomes

one more reason not to get out & walk.

Things like this park bench help build a stronger

culture of walking in the community.

Deaths by automobile per million citizens:

USA: 119.7

Italy: 55

France: 52

Spain: 36

UK: 28

So the US, purportedly the safest nation according to accepted standards, is actually the worst in this sample, and by a large margin! The most unsafe nation in the sample other than the US is Italy, where it’s standard practice to pass a car on a highway approaching a hilltop beyond which you cannot see, and Italy is more than twice as safe as the US. The safest country in the sample is the UK, which is more than four times as safe! If you average the non-US nations (42.75 deaths/million) and take the difference between that and the US multiplied by our population, then the logical conclusion is that our traffic engineering standards are killing about 23,000 people per year in the US! As with fire standards, traffic engineers should be embracing traditional urbanism with open arms because it saves so many lives per year!

On the divide between traffic safety and fire safety, consider this: if you only count deaths by automobile of people walking and people cycling, that’s 19.4 per million in the US, which is almost 50% more than the egregious 12.4 per million deaths by fire in the US each year. To be really blunt, if every fire department in the US closed up shop and dedicated themselves to reducing deaths of people walking and biking to zero, 2,100 lives would be saved in the US every year. Over my lifetime of 57 years, 119,700 people we’ve buried or cremated would have lived instead, with not a single fire station open in the US. To be clear, I’m not advocating for that. What I am advocating for is for fire chiefs and fire marshals to open their eyes and realize that when they do something in the interest of fire safety that damages walking and biking safety, they’re likely killing people!

Look, I understand that neither the deputy fire chief nor traffic engineer overseeing Celebration are evil people, intent on killing their neighbors. And I hope both of them are reading this. It’s likely that you guys got into your lines of work at least in part because you’re interested in helping people, and making them safer. But the standards of your specialties, because they focus so tightly on just a few specialized metrics like LOS are actually killing and maiming people, destroying families, and causing uncounted grief. Your ideals are not wrong; your ideals are good. It’s your standards that are egregiously wrong, and causing much suffering. Do the right thing, and reconsider your standards. Let Celebration live, and may each of you stand as change-makers against unsafe regulations. Make places safer in real life, not in your tiny silos. The time is now.

~Steve Mouzon

Great Storefronts

search the Original Green Blog

It may come as a surprise, but few things in walkable places are stronger predictors of the vitality of a town or neighborhood center than the quality of its storefronts. Centers in the US normally gather around a Main Street or square. European centers often gather around a plaza, place, piazza, High Street or (again) a square. But whatever it’s called and however it is shaped, the life of the center is fueled more by the quality of its storefronts than by any other factor. Auto-dominated commercial strips, by contrast, are fueled most by two things: their tall pylon signs, and tall architectural elements such as towers at the corners of mid-box buildings which are designed to attract attention quickly from motorists speeding by. Big-box buildings, of course, are their own massive billboards. But back to walkable places...

Go into any neighborhood and walk down a primarily residential street, and you’ll likely find relatively few people walking, even if it’s after work. But good neighborhood centers are often thronged with neighbors after work. A few of the people on the residential streets are walking to a neighbor’s house, but most of them are walking to the neighborhood center. The primary job of the residential street is to collect them and to entertain them enough along the way that they don’t get bored before arriving at the neighborhood center.

Think of the primarily residential streets as the opening act to the main event that is the town or neighborhood center. Streets leading to the center should have enough Walk Appeal to be interesting so that people keep walking; the center itself should be positively entertaining in order to entice enough people that it becomes a vibrant place.

Entertainment begins at the storefront, and the reason why is primarily geometry. As you walk along the sidewalk, the views that change most quickly are those into the storefronts beside you. Every five to eight seconds, you can walk past another shop, with its unique selection of wares on display. Entertainment is the opposite of monotony, and changing the view frequently is essential to avoiding monotony. All of the places shown in this post are in metropolitan areas that have districts built of larger buildings, but fewer people walk there except at starting time and quitting time of the offices because large office buildings are much less interesting because it can take a minute or more to walk by some of them.

People don’t come to the center solely for an entertaining walk, of course; they usually have a reason to visit one or more of the shops. So uses do matter, and the the more frequently-visited businesses like a grocery or a third place (coffee shop, bistro, cafe, pub, or restaurant where you can bring your laptop or tablet and hang out for awhile) draw people more frequently than a shoe store, for example. The difference is that if the walk is boring or the storefronts in the center are boring, they’re more likely to drive to the shop from which they need something, pick up the item, and drive back home whereas with great Walk Appeal fueled by great storefronts, they’re more likely to walk and then stay awhile once they get there, benefitting more businesses.

We’ve already talked about frontages in general; now let’s look in detail at the storefronts that line those frontages. And fortunately, there are a few simple steps for making them enticing. Storefronts are made up of up to five parts. Three are essential and two are optional. The building face is essential, and includes the windows, doors, doorways and other architectural elements. The interior display is essential as well, as a storefront where you can’t see what is being sold is pointless. Signage is also essential. Many storefronts have some sort of shelter, such as an awning, gallery, colonnade, or arcade. Some storefronts include exterior seating for food or drink service establishments. We’ll look at the essential elements of a storefront that occur on the sidewalk level in this post. The following are rules of thumb for each:

Building Face

Windows & Transoms

Storefront windows should be single-lite clear glass to best display the wares inside. Divided lites may be used only when the items for sale are substantially smaller than the panes, so you can get an unobstructed view of things in the window. Storefront windows may run the entire height of the glazing, or may be capped with transoms. Transoms may have divided lites because the muntins diffuse light coming into the shop, bathing things within the shop in a softer light.

Glass Percentage

The best storefronts are 65% to 75% glass at eye level. Less glass is boring, because you can see less of the interior. More glass is also boring, but for a different reason: the closer you get to the 100% glass of a butt-glazed curtain wall, the less interesting the wall becomes because more and more architectural elements like piers, pilasters, casings, and sashes must be removed. And when walking down the sidewalk beside the curtain wall, you’ll notice that glass becomes more reflective when viewed from a steeper angle. The glass that’s 30 feet ahead of you essentially becomes a mirror, so you can’t see inside.

Window Sill Height

Storefront window sills should never be higher than 29 inches, which is table-top height in a restaurant. Higher sills restrict your view into the store. But glass should never run all the way to the sidewalk, either, because the lowest few inches of the wall take a lot of abuse. A sill constructed of something tougher than glass should be a minimum of 6 inches tall. Sill heights should vary from store to store because that is more interesting than holding all of the sills at the same height.

Window Head Height

Window heads should be no lower than 8 feet above the floor, although they can be much taller, running all the way to the bottom of the storefront beam if desired.

Storefront Doorways

Doors in commercial buildings are usually required to open outward by fire codes, but if the door is located at the edge of the sidewalk, someone walking quickly by on the sidewalk can be seriously injured by a door unexpectedly opening. This happened to a friend of mine; the end of the door caught him square in the forehead, splitting it open. I had to take him to the emergency room to get stitched up. So always set storefront doors back at least three feet deep into a doorway. The doorway sides can be either square or splayed display windows. A doorway isn’t just a safety device, however; it’s the best display space in the shop because it’s where people are slowing down to go inside, so they see the wares better. It’s also a good place to stand temporarily in the event of a rain shower.

Storefront Doors

A storefront door should be mostly glass, and may be either a single lite or have divided lites of any pattern, because it does not have to provide a clear view to merchandise just behind it, as that floor space is used for walking, not for display. Storefront doors may be single or double, and should be distinguished from the windows in some way in order to be immediately visible to people walking by. Paint color is a common method.

Storefront Beam

The storefront beam holds up the wall above, and the span between visible supports is fairly long: at least 10 feet; often 16 to 24 feet or even more, so the beam needs to be deep enough that it’s obviously strong enough to carry the load. The storefront beam may be a visible steel beam, or better yet a steel beam built up with plates, angles, and rivets, which is more interesting. Or it may be clad with stone, terra-cotta, or other finishes.

End Piers

The end piers occur at the ends of the shops (and occasionally in between) and visually support the storefront beam. End piers may either be shared between two neighboring shops, or each shop may have its own end pier that abuts its neighbor’s end pier such as these storefronts (which also have intermediate piers as well). The decision of whether to use shared piers or individual piers is usually made on a block-by-block basis and is based on whether the developer is building several shops at once (where shared piers work) or whether each lot is individually built out (so that individual piers are required).

Interior Display

This element should be obvious, but in today’s retail climate, it needs some explanation. Retailers should turn their wares toward the windows where everyone in the neighborhood will see them, instead of inward where only those who are already inside their shop might see them. This should be Marketing 101. But retailers complain that “my store is designed to put shelves on the outer walls, so that all the aisles are double-loaded.” This is easily fixed by simply flipping aisle and shelving. Rippled across the store, this creates the same efficiency, but with the outer aisles getting many times the exposure through the storefront windows.

What they choose to display on those outer aisles is important. In my neighborhood, there is a grocery store which did the right thing and put windows all along the side of their store. But then they chose to display stuff like diapers in those shelves. One aisle away is their wine department. Imagine how much better they would do if they turned more enticing products like that toward the sidewalk instead of diapers!

Signage

I’ve written a Sign Code for Walkable Places, the essence of which is this: Signs for places where people walk should be scaled to the person walking by close to the storefront, not the automobile speeding by a hundred feet or more from the storefront. This means that you’re permitted more types of signs: blade signs, band signs, window signs, etc., all on the same storefront. The problem with signs in auto-dominated places is that they must be very large to be seen and read before you zip by in your car. So it’s essential to limit the area of the signs in auto-dominated places, and also the number of them. Signs in walkable places can be much smaller, because you see them from short distances. As a result, they generally don’t need size limitations, or limits on sign types. And their variety makes a place more interesting.

~Steve Mouzon

Preserving Architectural Character in Places Threatened by Sea Level Rise

search the Original Green Blog

Preservation is a losing battle, and nowhere is this more obvious than in South Beach. Eventually, every building ever built will be lost, so preservation needs to be understood as the act of extending the lives of places and buildings we love the most, not the act of preserving them forever. Every thriving place has development pressure that seeks to replace old buildings with new ones that are substantially larger. Anyone who lives in Miami Beach and who wants to visualize development pressure can simply walk outside, look around, and count the cranes that dot the skyline. Preservationists have gotten relatively good at fighting back against development pressure, at least for the best historic buildings, but the pressure is there.

Sunny-Day Flooding

Here on South Beach, we have another threat to the character of our architecture, and it’s not yet clear if this threat can be opposed, at least for some of our buildings. That threat is sea level rise. When Wanda and I first moved here almost 14 years ago, “tidal flooding,” and “sunny-day flooding” were terms we didn’t hear for several years. Tidal flooding wasn’t a thing until 2009 or so. But by 2013, we were having nights like this on an accelerating basis, when the sea level was simply higher than the streets, with seawater spilling into the streets. Inland people debate sea level rise, but not South Beach residents because we have seen it with our own eyes.

Even before the October 2013 flood occurred, the city had undertaken a massive infrastructure project consisting of improved storm drainage, huge underground storage tanks, and massive pumps to pump the water back out into the ocean before it gets to street level, putting us in the same boat as New Orleans: cities with streets that are at least sometimes below sea level. And those pumps work almost all the time, but when they failed after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans flooded and thousands of buildings were lost. So far, the South Beach pumps have not failed, and we have had no further street flooding. But we inevitably will at some point.

Raising Streets

And so the city is now raising the streets. Land is highest on the Atlantic side, sloping down to the lowest point on the bay side. Streets are being raised about 3.5 feet on the bay side, which is the existing grade near the middle of the island.

Unfortunately, the city is not raising the buildings. I predicted last year that this approach would cause rain-driven flooding problems, and this has already happened. Here’s why: when the streets are raised but the buildings are not, those buildings may be 3 feet or more below the sidewalk. In a rainstorm, if debris like cardboard clogs the newly-installed storm drains in front of a building, or if mulch washes out of a planting bed to clog the drains, the lower area at the front of the building effectively becomes a swimming pool, and in many cases the only place for the water to run is into the building. The pumps might fail only once ever few decades; this flooding could happen repeatedly; whenever there’s a big storm. The city worked with the insurance companies on the first floods in Sunset Harbor, but the insurance companies will quickly tire of the same story each time floods occur. At some point, the buildings must be raised because they will otherwise become uninsurable. These are discussions we need to be having now. The longer we wait to start talking about how to raise the buildings, the more painful and urgent the process will be. The new administration should make this a high priority, as we cannot avoid this problem indefinitely.

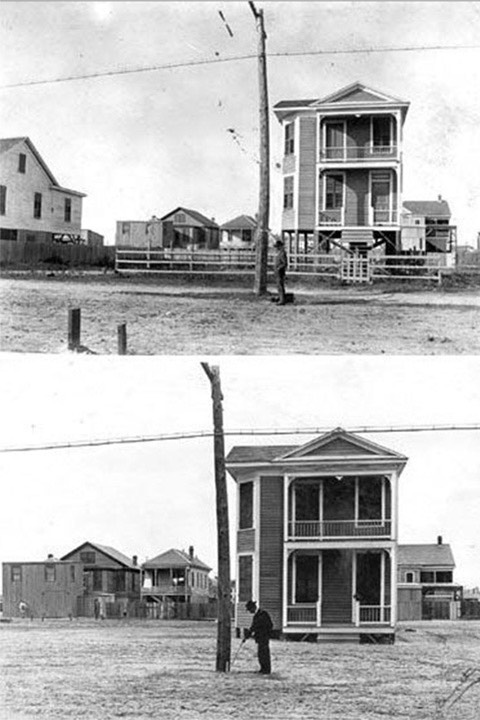

Raising Buildings

Galveston house before and after

being raised

We’ve done this before, and with masonry buildings, not just wood-framed houses. And we should be doing this now on South Beach, as our ancestors did in these two examples: Bay Village in Boston was raised in the 19th century after the Back Bay was filled in. Some areas were raised up to 18 feet, although some of the building main levels became basements. After the Galveston hurricane of 1900 (the deadliest natural disaster in US history) the entire city was raised up to 17 feet, which is the current seawall elevation. So there’s no doubt that we can raise 1- and 2-story buildings.

There’s also no doubt that we cannot raise skyscrapers. For tall buildings, the best solution will probably be to demolish the second level and move the first level upward, leaving upper levels unchanged. The problem is the “Sour Spot” between the 1-2 story buildings (or maybe 3) and the high-rises. Sour Spot buildings that are too tall to raise but too short to modify are likely to be lost. It’s simply an economic reality. With sea level rise happening across the country and around the world, it’s unreasonable to expect anyone to bail us out because this is not a localized disaster like a hurricane. We’re on our own on this.

Walk down Ocean Drive, and you’ll see that some of the most memorable examples of South Beach architecture are in the Sour Spot and likely to be lost because they’re too tall to raise but too short to move the first floor upward. Ocean Drive Sour Spot buildings won’t be the first ones lost, as they’re sitting on higher ground; that’ll happen further back in the Art Deco District at the beginning. But no reasonable models today project a future where seas don’t continue to rise to and beyond Ocean Drive at some point.

The Replacements

replacements built in wealthy times… a random

collection of styles that just happened to be

popular at the times they were designed

When this happens… and there is little doubt but that it will… what will replace these long-loved buildings that form the core of the character of South Beach? If we do nothing to direct the character of the architecture, those replacements will almost certainly be a random collection of “styles du jour” that occur at the times at which they will be built. In short, we’ll morph over time into urbanism no different from any other urban beach city in the US, without the strong character Miami Beach has today that leaves little doubt in any visitor’s mind precisely where on earth they are.

replacements built in frugal times

It is rare for a city to have strong architectural character, and it helps create far greater value than exists in more ordinary places. And that strong character draws millions of people to travel from around the world to visit Miami Beach every year. Will that continue once that character is eroded beyond recognition? Sure, the Post Office will be preserved, along with a few other Art Deco monuments, but what city that was thriving from 1920-1945 doesn’t have a few Art Deco monuments? Once the Sour Spot buildings are replaced by random architecture, we will clearly lose great real estate value and great annual revenues to local businesses.

Coding for Character

Architect Trigger Warning: I’m about to trigger some foul emotions in the architectural community. There is a solution, and that is to code for character. This means that leaders in the city must make the choice to build future buildings that become part of a new living tradition of Art Deco architecture. If Art Deco is what people love, why not build more of it? Most architects will fight this furiously, kicking and screaming all the way. Their battle cry is “architecture must be of its time!” The fact of the matter is that there is a strong track record of cities coding for a particular character, and it usually creates great value.

In some cases, coding for character takes the form of an "extreme makeover” such as when Santa Fe chose about 1910 to transform from a town of Victorian cottages to the adobe city it is today. Santa Barbara chose a makeover to Spanish Colonial Revival about ten years later. South Beach, as we all know, adopted Art Deco shortly thereafter. In other cases, places like the French Quarter in New Orleans and Charleston have chosen to code for character in order to preserve their existing character. In every case, strong character has created strong value.

Design Leadership

Who should lead this initiative to ensure preservation of the character of Miami Beach into the future? It’s not set in stone. Here, the Art Deco character was established by a community of architects such as Lawrence Murray Dixon. Architects also led the Santa Barbara transformation. Architect-driven initiatives do not have to be large at the beginning. Just a few like-minded designers can band together to get it started. The Sarasota School of the 1950s is another model where there was not a code per se, but rather a collection of architects agreeing to pursue similar architecture. The code, however, is stronger.

Civic Leadership

The initiative to preserve character can also be led by civic leaders. Mayor Joe Riley in Charleston is a great example of the “strong mayor” model. Leadership can also come from someone on the Commission that adopts the initiative as their own. The Chamber of Commerce can lead as well, as they did in Santa Fe. The bottom line is that there are many people who can step up to the plate and get the initiative rolling to preserve the character of Miami Beach. Who will it be?

~Steve Mouzon

Hypocrisy and the CorbMiesian Revival

search the Original Green Blog